On Monday this week, the Sun let off a huge solar flare. That's a massive explosion on its surface. Surprising as it may sound, the Sun has a magnetic field, just as the Earth does - but it's not static. Sometimes, two magnetic fields which previously weren't lined up can suddenly realign themselves, releasing a huge amount of energy. Matter on the surface of the Sun can suddenly be accelerated to close to the speed of light. If the event is powerful enough, this gives rise to a coronal mass ejection - a great burst of matter heading out of the Sun.

Now, at 93 million miles away from the Sun and comparatively extremely small, it's not often the Earth gets in the way of coronal mass ejections. But occasionally we do - and this is just what's happened this week. The matter, of course, does not travel at light speed, so we get a few days' warning.

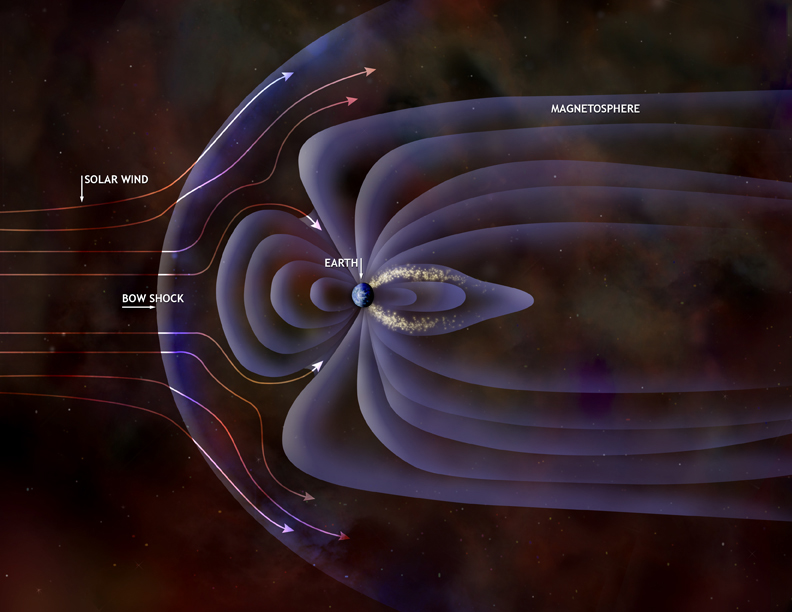

What happens when such a thing hits the Earth? Don't worry. Nothing lethal. Because all these particles are charged, they're affected by magnetic fields - and Earth has one of those too. This is what happens:

(From Chandra.)

(From Chandra.)Incidentally, Jupiter and Saturn too have spectacular magnetic fields and aurorae - indeed, Saturn's magnetic field might be responsible for all kinds of odd effects among its moons.

Although Earth's magnetic field directs the charged particles away from most of the Earth, it directs them towards the poles. But those don't suffer mass destruction. Rather, they shimmer with the Northern Lights, or the Aurora Boreolis.

The Aurora over North Norway, from APOD.

The Aurora over North Norway, from APOD. The Aurora from above, photographed by astronauts aboard the Interntional Space Station. APOD.

The Aurora from above, photographed by astronauts aboard the Interntional Space Station. APOD.I went to Norway when I was 20 but have never seen the aurora, and that's one of the things I really long to do. It annoyed me that Philip Pullman turned it into something supernatural in "Northern Lights", but he certainly expressed a silent, throat-tightening beauty about it that made me want to go and see it even more. They move around - I don't know how fast. The green light is from excited oxygen atoms. "Excited", in this case, means that one or more electrons have jumped up to a higher energy state (you can think of that like jumping up to a higher electron shell). More rarely, it emits red light. Nitrogen, too, glows in different colours - blue and red. There's a nice little description of the chemistry here.

A coronal mass ejection is not needed to produce the aurora - it occurs anyway because of the solar wind. The Sun is in fact hurling ionised matter at us all the time. A coronal mass ejection is just a great glut in one go. This can result in the "northern lights" being seen much further south than usual - it seems they have already been seen in Northern Ireland.

The problem with coronal mass ejections is that they can disrupt communications. In November 2003 there was a particularly large one, which was not only hazardous for space observatories such as SOHO but also for aircraft. There's a good write-up in the introduction Dr Stuart Clark's "The Sun Kings" about the things that took place then: radios that aided expeditions, forest firefighters, marine emergency calls and the like became unreliable; aircraft had to fly below 25,000 feet and at a lower latitude than north Scotland; Sweden suffered blackouts; nuclear power plants in America reduced their power in case of damage. Compasses, too, no longer knew which way was north and swung about wildly. As luck would have it, Cassini, ten times further away, got a bashing too!

Infuriatingly, I missed this whole thing. I was in Granada, southern Spain, at the time, on a year abroad for my degree, and only using the Internet in cafes every few days (Galaxy Zoo did not then exist and I didn't even hear of Facebook for another few years). I think it must have been around Halloween - I recall walking round Granada with a friend terrified of masks that night, and listening to her worries about love and commitment. Then the 2006 solar eclipse happened when I went back to Spain for a TEFL course - we would only have seen a partial eclipse, but I missed it then, too.

The most spectacular coronal mass ejection to hit Earth on record is the one that occurred in 1859 - again, as detailed in Stuart Clark's book. In that one, auroras appeared, it seems, all over the planet. You could read a book at night - if you weren't busy being terrified of the end of the world, as it seems many people were. Hilariously, however, there were so many charged particles in the air that this happened:

Boston telegraph operator (to Portland operator): "Please cut off your battery [power source] entirely for fifteen minutes."I first heard of this conversation in an Astrofest lecture - it was especially amusing because the lecturer showed us the code used first! In any case, it's rather like an msn conversation with the Internet switched off (so if anyone tells you that the Internet's a new and unnatural thing, remind them about telegrams).

Portland operator: "Will do so. It is now disconnected."

Boston: "Mine is disconnected, and we are working with the auroral current. How do you receive my writing?"

Portland: "Better than with our batteries on. - Current comes and goes gradually."

Boston: "My current is very strong at times, and we can work better without the batteries, as the aurora seems to neutralize and augment our batteries alternately, making current too strong at times for our relay magnets. Suppose we work without batteries while we are affected by this trouble."

Portland: "Very well. Shall I go ahead with business?"

Boston: "Yes. Go ahead."

Coronal mass ejections do not appear entirely randomly. The Sun has a cycle of its own: an eleven-year period that alternates between a "quiet" time of mostly steady shining, and a less-quiet time of more sunspots and flares. These changes correspond to changes in solar output - in other words, how much heat and light we get. There have been efforts to link this changing activity with climate change, but the trends are weak - if that. In the short term, it does work to some extent - there have been arguments for decades over whether you can correlate solar activity with the price of wheat. And it is possible that a few decades of warmth or chill (the Little Ice Age; the time Britons grew grapes, etc.) are due to changes in solar activity - but they were not global events but local ones, suggesting that conditions on the Earth itself, just like now, were the driving forces in those cases.

Going back to Stuart Clark again (as you can see, I must finish his book - I'm the dreadful kind of person who starts six books at once and falls asleep while reading them, awarding myself an ever-more-toppling booklist!), he has this to say about studying the Sun and its eleven-year cycle:

Like a heart, the Sun pulsates. This is not a visible movement but rather a gradual buildup in strength and subsequent weakening of the giant magnetic bubble that emanates from within the Sun and surrounds all the planets. As befits a celestial body of some 4.6 billion years in age, each one of these magnetic heartbeats takes a leisurely eleven years, or thereabouts, to complete.In any case, things are looking interesting. National Geographic says this is the largest flare for some time. Aviation Week has some mind-boggling pictures of what our local star is up to right now:

So, in the average career of a scientist, he or she can expect to see this happen four times. This makes understanding the Sun as difficult as a biologist trying to deduce the life cycle of an unknown creature by observing it just long enough to witness four beats of its heart. As a result, solar astronomy is a multigenerational science. Each new cohort works to build a finger legacy of observations for those yet to come.

Pete Lawrence got an astonishing photograph of the flare. You can also watch a quick clip here on the BBC. And check out AuroraWatch to see if it might be worth nipping outdoors . . . please let me know if you see anything!

PS And if you are really into solar storms, you can now join Solar Stormwatch to map them properly. It's concentrating on past ones - but Zooites work through things very quickly, so you never know, soon enough you may be working on them as they happen!

2 comments:

i have been always amazed with functionalities of all existing planets in our universe. do you think that there could be an another living planet outside earth. waiting for the day to see my assumptions go live

Other worlds are in ours. Fantasy is the theory of the "Why not?". Reason and science, such their witness.

Post a Comment